A small book sample from my Sex Positivity series' upcoming Demon Module, "Radcliffe's Refrain" gives a quick rehash of the demonic trifecta (damsels, detectives and sex demons) vis-à-vis Ann Radcliffe's pioneering of it. Also talks about her history as "mother to the Gothic novel" and problematic legacy following her disappearance.

Originally shared on my 18+ website on 1/25/2025: https://vanderwaardart.com/2025/01/book-sample-exploring-the-derelict-past-opening-and-radcliffes-refrain

Radcliffe's Refrain (reprise)

Especially popular or remediated characters tend to get virally shared. Such sharing can be hard to regulate or track. In this case, we not only have detective pastiche, but Velma pastiche. Seriously, this foxy nerd is legion, but also a regular practitioner of the "explained supernatural" trope originally formalized by Ann Radcliffe. Defrauding the "supernatural" through spooky piracy is a common theme in Radcliffe's works, or embattled marriages, false relatives and various ordinary things taken to performative extremes; e.g., the mother being sent to live in a nunnery for the rest of her days. To this, Radcliffe was following suit with Walpole, injecting the supernatural into ordinary events, getting at the truth of things through outrageous narratives that still, in the end, feel cliché and homely.

—Persephone van der Waard, Sex Positivity, Volume One (2024)

(source: Women's Museum of California's "The Mother of Gothic Literature," 2017)

Celebrated for marrying the Romantic and its posturings of the Sublime and nature with a modest, enchanting Gothic, Ann Radcliffe was a rockstar of the early Gothic novel. Often called its "mother" and prone to crossing pens with queer troublemaker, Matthew Lewis, the curious irony with Radcliffe's torturous demon lovers, as described by Cynthia Wolff (re: "The Radcliffean Model," 1979), is how they weren't magical behind her Black Veils. Yet, the banditti of the Great Enchantress did personify the same dark desires more spellbound (and queer) enchanters happily conjured up (re: Lewis). The Final Girl dodging mutilation mid-courtly love also stems from Radcliffe's work, the Gothic heroine/damsel being the original scrapper who would evolve from detective to nep-conservative, peace-through-strength fighter by armoring her virtue from alien forces with brawn. It's black-and-white, Cartesian to the core, and prudish to boot.

To that, whereas Shelley was a bred-to-the-bone radical who embraced the alien and fucked with it/wrote like a bereaved mother and whore, Radcliffe wrote like a virgin[1] who had no idea what loss or surviving open, punch-the-witch persecution was; i.e., like someone who was afraid of sex/never had it (she was married, but to my knowledge never had kids). Instead, it's something to abject and attack/dissect, because sex = death and rape is around every corner. There's a kernel of truth to her stories, but like all conservatives, Radcliffe completely misses the historical-material critique to perpetuate its symptoms through police force inventing enemies (re: black rape myths). She's the fatal portrait of the Tories, her Gothic immature versus mature.

So if Shelley made demons, then Radcliffe investigated them (without whom there'd be no Scooby Doo [or drug-like Scooby "snacks"] without Radcliffe, or Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys, Alien, Halloween, Texas Chainsaw, or Murder, She Wrote); if Shelley single-handedly started science fiction, then Radcliffe's novels—starting with The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne (1789), and going onto more successful stories like The Romance of the Forest (1791) and The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), canonized the detective story wedded to "respectable" and "successful" Neo-Gothic cliché (e.g., folie-à-deux, or mass hysteria, in The Italian):

Ann Radcliffe was a pioneer of the gothic literary genre. Her inspirations were The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole, often named the first gothic novel; The Old English Baron (1777) by Clara Reeve, and The Recess; Or, a Tale of Other Times (1783–1785) by Sophia Lee (Miles, 2004 4). By the time she published her successful novel, The Romance of the Forest in 1791, gothic fiction was considered "the trash of the circulating libraries" and a "cheap and tawdry form of entertainment" (Townshend 2014). However, Radcliffe was considered to be an exception, she was lauded by her contemporaries as "the Shakespeare of Romance writers" and as "a genius of no common stamp" (Miles, 1995 7; Barbauld, 1810 i). Radcliffe single-handedly changed the gothic novel; it was by her inclusion of original poetry as part of her novels and as epigraphs, as well as her elaborate descriptions of landscapes, that she elevated the form [emphasis, me, for its problematic nature]. Critics agreed that Radcliffe had moulded pre-existing literary components to refine a "new, powerful, and enchanting" genre of literature (Miles, 2004 4) [re: Victoria DeHart's "The Enchanting Ann Radcliffe," 2020].

Radcliffe didn't make monsters; she exposed them—i.e., as false, solving mysteries to turn things back to normal. Her stories manufacture dilemmas whose middle-class solvings always benefit the status quo. For all her skill, she actually kind of sucks. She's not "a nice old lady"; she's an opportunist—one using police language to adopt an air of authority leading her audience around by the nose.

In a nutshell, then, Radcliffe wrote cop fiction with "haunted" houses, venerating private ownership/assimilation (secret princesses), and inventing state enemies through bogus propaganda stories: "White Middle-Class Lady Investigates Whoever Killed the Rich Landowner." As a queer an-Com, I find her writing deeply unsexy because, in the absence of shock, she's lecturing about morals in a PG-grade adventure story that has the same negative effects it would inspire, offstage. It says little of value, but value judges everything. Even the fucking trees have value (eat your heart out, Tolkien)! Even so, it's still useful for putting a finger on the middle class' pulse/desire to scapegoat their victims during Capitalist Realism.

Radcliffe the woman is far more mysterious (and conservative) than Shelley. Likewise, her legacy is far more problematic (and no less complex). For starters, Radcliffe took precautions to conceal her identity and wrote from absolute secrecy. She avoided scandal like the plague and wrote stories that maintained privatization, and she was indisputably a master of suspense and gaslighting her audience (who she loved to torture through the Black Veil "MacGuffin" nearly two centuries before Hitchcock stole it). Forget Scooby Doo—without Radcliffe, there would be no Clue, Agatha Christie, Poe, Hitchcock, Lovecraft, or Stranger Things, but also no Perfect Blue (above, 1997) or The Vanishing[2] (1998). There'd likewise be no J.K. Rowling (who, apart from Harry Potter, also writes bigoted detective stories), hence TERF stories, on and offstage, transvestigating aliens killing people and blending in (re: men in women's spaces[3]). For better or worse, Radcliffe well-and-truly broke the mold/"made it," in that respect, and heavy lies the crown. Suitably enough, she was also a huge xenophobe and opportunist, abandoning magic for enchantments of a more phenomenological sort: spells of mystery and perception. Perception is reality!

Simply put, Radcliffe and similar authors—from Dacre to Rowling—have all thrived on demon lovers and sexual torture to triangulate/tokenize sex and force (through the process of abjection policing the ghost of the counterfeit as something to commodify the raping of through the American and European middle classes). And Radcliffe "started it," insofar as her School of Terror was the launchpad for a more troublesome series. Yes, she didn't show abject horror on par with Lewis, Giger and Scott. Even so, her stories are full of damsels, detectives and sex demons; i.e., her detectives—which are always damsel-esque/virginal—doggedly investigate what damsels endure through sex demons as "all over the place": torture, crime, death, rape, etc. And those—much like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016) went on to become much more violent, silly and sexy over time: "Velma Dinkley and the Mystery of the Boner-Inducing Dump Truck!" "It is a truth universally acknowledged that a baddie with a fat bedonk must be in need of a good monster pounding." Jinkies!

(source: DC Comics' "Scooby Apocalypse," 2020)

Except before we even begin talking about detectives and torture at length through the xenomorph as an "antique" doppelganger for Medusa, I wish to clarify two points and cover some history (three pages' worth) that will come in handy moving forward—not just for this subchapter or volume, but really for the entire book series as it presently stands.

One, "torture" is a very broad term. It can hurt or harm, hence threaten through exhibitionism and voyeurism promoting ritualistic punishment that allots the submissive tremendous power (under the right circumstances); those that harm or disempower workers are bourgeois, designed to pacify victims by chattelizing them in demonic language. This basic distinction not only amounts to canonical torture vs iconoclastic torture, but Radcliffe's blend of exquisite "torture" being immediately harmless but nonetheless problematic-yet-salvageable; i.e., bad play/coercive BDSM vs good play/sex-positive BDSM; e.g., unironic demon lovers like Ted Bundy or Count Monti exhibited by Radcliffe (and the American television networks) during criminal hauntology versus a demonic dom who is both trustworthy and actually wants to teach mutual consent through transgressive media.

We'll explore the latter dichotomy much more in Volume Three. For now, just remember what we said about criminal hauntology in Volume One (exhibit 11b2, summarized but indented for clarity):

Criminal hauntology relishes in the commodified suffering of the buried; e.g., the gays as automatic criminals, perpetual fugitives/victims, and unironic closet monsters (the xenomorph being the combined forces-of-darkness black knight, dark torturer and cosmically queer rapist at the same time, exhibit 60d); conversely it gives sanctuary to canonical status-quo fugitives: the black or false penitent (the namesake of Radcliffe's Italian).

Two, detectives are classically cops, including—in a sense—those who embellish them through relatively conservative fiction: the white woman's murder mystery or noir about soft-to-hard-boiled, nosy dames with brains, brawn, and courage, but also the Gothic staples of a flashlight, threatened virtue, and (these days) various force equalizers (the Amazonian Persephone going back to Hell to attack state enemies). Cops defend property before people, and detectives of a female sort classically investigate rape as form of torture—effectively serving justice through an updated idea of the local constable or shire reeve as a manager of the estate; i.e., the person of material privilege doing the state's work. Detectives further evolved into modern cops/sheriffs in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, becoming militarized (and tokenized, above) under the modern police state, courtesy of Pax Americana as informed by the likes of Radcliffe voicing the trend as a bank-making mystery women; re: through that of the white, cis-het, female weird canonical nerd, historically decaying feminism in defense of profit, capital and the status quo (re: Volume Zero, Radcliffe and the true crime genre as founded on the Neo-Gothic treatment of damsels, detectives and demons).

Regarding those points, some history (and an exhibit) to go with them exhibit 47a1, in a few pages): Before this crystallization, though, the idea spawned out of a hauntological engagement with an imaginary past that carried into the here-and-now by male and female authors of an emerging middle class: the Gothic novel as a medievalized property dispute investigated using darkly romantic abject language penned by persons other than aristocrats but not the working class; i.e., the home as both a medieval façade occupied by pre-fascist destroyers the likes of the black penitent, knight, priest or Italian count, and an uncanny chronotope pierced by the tried-and-true tradition of scholarship-turned-sleuthing of middle-class debutantes in the shoes of older imperiled maidens (Cartesian-dualism-in-disguise).

Detective monks, for example, were invented as a hauntological murder mystery centuries after the warrior monks of old (exhibit 48b); likewise, the female detective would go onto defend the state's notion of property as a hauntological anomaly thereof: a piece of property/ass who suddenly could think because she's had a middle-class education that, for all intents and purposes, was buoyed by the nation-state as a developing entity in its own right.

Partly the idea was to voice the concerns of the oppressed, but it was penned to pointedly voice those the state privileged over queer people, persons of color or religious minorities inside the state; i.e., the WASP (white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant) author of pre-fascist and minority scapegoats, which basically is what Radcliffe was: a female novelist who far outpaced her husband's income by writing fancy versions of the penny dreadful, then using the unprecedented "fuck you" money she made to retire from public life and live in relative comfort/seclusion. But, given her penchant for secrecy, this is largely speculation; re, DeHart:

In addition to being critically successful and popular, Radcliffe was England's highest paid novelist during the 1790s. She earned £500 for Udolpho (1794) and for her final novel, the Italian (1797), she earned £800 (Miles, 2004 4). According to Robert Miles (2004), Radcliffe's "nearest competitor" before 1797, was the playwright and novelist Frances Burney, who received £250 for Cecilia, Memoirs of an Heiress in 1782 (4).

Dale Townshend[4] and Angela Wright refer to Radcliffe's disappearance after the publishing of The Italian as the "Radcliffean Interregnum" (13).

[…] The literary world could not comprehend that the highest paid and most popular novelist of the 1790s had stopped publishing new material. In 1800, rumours began to circulate that Ann Radcliffe had died; and by 1811, false reports stated that she was restrained within Haddon Hall in Derbyshire, driven "mad" by the "morbid exuberance of her [own] imagination" (Smith 155; Miles, 1995 25). There is no clear reason for Radcliffe's disappearance, but scholars have offered different ideas; Townshend and Wright (2014) believe her interregnum may have been due to a combination of her frustration with the plethora of "Radcliffe imitators" in the market, and the mixed reviews she received for The Italian (13). Ann Radcliffe was also plagued with poor health in the last twelve years of her life (Norton, 1999 236) [source].

Personally, I think she sold her soul to the Devil, who told her to "just write about trees, dude" and eventually came to collect—dragging Radcliffe down to Hell to sodomize her just like she always wanted to write about but didn't. Truth is stranger than fiction (you did always tell to write for myself and my audience, Dale, and it was good advice)…

In all seriousness, Radcliffe was a middle-class novelist of critical acclaim and financial success, who—after a relatively short career (eight years) writing about the English countryside "but with bandits" (a very British thing to do) and treating sex like a disease (also a very British thing to do)—retreated from the stage of writing and political activism altogether (a bit like Bilbo). She's the kind of person you hear being accused of "terrorist literature" (re: Groom), only to look into it and learn that—in all actuality—Shelley was closer to the mark, and Radcliffe nowhere near as interesting or critically impactful as Frankenstein. Radcliffe's Black Veil was famously a giant MacGuffin—a largely empty illusion between a lot of expert shadow play and pre-Victorian soap opera setting the stage for the invention of Gothic terrorism Crawford warned about (re: "The Invention of Gothic Terrorism," 2013). More matter, less art, queen!

Clearly, Radcliffe is someone I have mixed feelings about. I admittedly enjoy her suspense and mood; her distinction of terror and horror in "On the Supernatural and Poetry" (1826) remains incredibly useful; and the use of poetic epigrams in her novels was something that inspired me (though I took as much inspiration from Lewis, in that respect). Even so, her contributions are all nuts-and-bolts devices and virgin/whore, us-versus-them dreck abused through capitalist fear and dogma she encouraged similar to Tolkien's later racism; i.e., she summons immigrant threats, then marshals police agents to discover and exterminate them: as someone who—of the middle class—enjoys imperial heritance, but needs to whitewash her own colonial guilt (and fete a good wedding at the end, with dancing peasants who just love being ruled by freshly-unveiled princesses).

That being said, I've already torn her corpse a new asshole in Volume Zero, so I'll spare everyone a sequel, here; i.e., in this refrain, I'll refrain from dragging Radcliffe any more than I already have, because we're ultimately going to be salvaging her work! Believe it or not, there's a lot of good ideas inside, especially with demon BDSM (which evolved through my work into ludo-Gothic BDSM). Likewise, Radcliffe clearly has her place in the history books, and The Italian is pretty neat, overall, but she's too high-minded/gutter-averse, and writes about trees to much. "Oh, wow! Another tree! Great[5]! Maybe we should do something about climate change instead of acting like they'll last forever?"

Again, Radcliffe wasn't a whore, she was a cop, thus a pimp. There's certainly value in detection regarding domestic violence and material dispute, but anchoring it in a society that's ultimately regressive isn't activism; it's conservatism, thus criminogenic. Despite the appearance of unreactivity, then, Radcliffe's class character isn't inert like helium, because white moderacy is always shadowed by a reactionary core: the exquisite "torture" of squirming during the abjection process and ghost of the counterfeit behind her Black Veil empty threats vanishing like dreams once exposed. It's proto-fascism and -Red-Scare/Capitalist Realism in its infancy. To it, she's the great ancestor of Margaret Thatcher(!): a xenomorph (shapeshifter) chicken hawk, having kids do her dirty work for her by becoming monsters to fight monsters and maintain state control (also, the makers of Stranger Things are Zionists and child abusers; re: Persephone van der Waard's "Welcome to the Fun Palace," 2024).

The fact remains, Radcliffe did give birth to monsters: witch-hunters-in-disguise! Through DARVO and obscurantism, her kids aren't saving the day by getting those pirates; they're privileged brats part of a larger scheme that creates and assigns criminality as something to imitate and exploit. And that's a trend that Radcliffe inspired/self-reported on before running and hiding from criticism, ultimately being unable to confront or explain it because she can afford to disappear during moral panic (re: the French Revolution); that's her legacy. It's a little pathetic, but also underused in terms of what can be used to help workers, not titillate consumers who ultimately grow more violent in pursuit of "dreaded evils." And that's what we're going to focus on, here: camping her canon, rape included! I'm excited!

As we do, remember how we're expressing our position within a society sick with moral panic (versus raising awareness); i.e., as actually policed by official or vigilante forces. Compared to us, followers of Radcliffe see strangers to attack—i.e., assign positions within society to alienate and kettle—per the terrorist/counterterrorist refrain (she literally founded the Gothic School of Terror): the girl whose superpower is survival, modesty (damsels) and detection, first and foremost, but also in latter-day examples, transformation into Amazons (sex demons) to have revenge for the state/nuclear family against the monstrous-feminine during abject moral panic—the pimp's revenge (often undercover)!

Cops are class traitors, and Radcliffe doesn't prevent crime, she causes it by "making jobs" about making jobs (on and on). Luckily there isn't a monopoly on these things, meaning the final function of the damsel, detective and sex demon isn't to police the alien through force. We can reclaim it by camping Radcliffe's canonical exquisite "torture."

At times, her calculated risk/revenge even has the right idea (sexual tension and play through Gothic poetics) but she quit far too soon to master that aspect of it. Woulda, coulda, shoulda. We'll build on said ignorance to salvage her wasted genius towards applied knowledge; i.e., ballooning its valuable aspects according to a system she helpfully adumbrated. The language of danger is useful ("Pull your team out, Gordon…"), ours and Shelley's proletarian pirates challenging Radcliffe's bourgeois ones. In short, there's a solid material critique in her stories—one that inverts, easily enough, to serve workers!

We'll consider camping Radcliffe, in the pages ahead, and will do so while keeping her privilege and ignorance in mind—but also her dazzling brilliance giving the game away (as Scott does, in Alien). Basically Radcliffe was a member of the imperial class, shamelessly pandering to their socio-materially constructed idea of class and place as under attack, post-colonization (re: paradise lost); and anything Edward Said wrote about Austen in Culture and Imperialism (1993) easily applies to Radcliffe and her own novels bougie sensibilities (which Austen also made fun of; re: Northanger Abbey). It's Goldilocks Imperialism, enchanting Old Blighty with a straight white lady's idea of "spectral enchantment" while belonging "to a slave-owning society." She probably bought sugar on purpose (with abolitionists buying honey instead; re: to protest the Caribbean slave trade).

(artist: Claude Lorrain)

Needless to say, Radcliffe certainly had talent and respect; she was also gentrified and conservative (as were the people who respected her[6])—was, by my account, an entitled sellout who abandoned any notion of whistleblowing to spend the next nearly-three-decades years in total reclusion. But even when she did write, she merely used the true-crime twist to scapegoat (xenophobic) symptoms of the structure in crisis, not the structure itself as always in crisis; i.e., not only did she partake of the unironic "bury your gays" trope by having no earthly idea what sex-positive queerness was, but her happy endings, post-corruption, supported the status quo by ending or exposing isolated pockets of corruption which, itself, is a harmful centrist myth.

Since then, the conservative opinion remains that all women are still property not persons, with those who become more active being treated as "phallic women"; i.e., less the sexual zombie, demon or whore and more a subjugated Amazon who had to prove she wasn't either of those things, nor a rogue huntress corrupting the nature of society concerning white women as a "protected" class: the jilted, furious seeker of ancient revenge (which, from the non-WASP perspective, is exactly what the xenomorph represents). This settling of old scores can be weaponized against women through the idea of virtue as well as vice—i.e., as Dacre's Victoria arguably was—but also against the queer community as something whispered about and conflated with "true crime" alongside the usual suspects/scapegoats. We fags are evil Italian Counts, apparently (a precursor to Dracula), awash in sin and medieval court intrigue leading to sodomy and murder.

Simply put, it's repressed, internalized bigotry and self-hatred, which the copaganda of the regressive Amazon attempts to destroy to prove her worth as a "good woman"; i.e., serving the Man by killing society's scapegoats (through exposure): both its fascist elements (demon cops/black knights and crooked authority figures who betray the fact that the structure is corrupt, thus must be dealt with) but also the targets of moral panic at large—in short, what would become Marx's spectres some forty-odd years after Radcliffe penned her final novel, and the Red Scare and similar states of panic that haunt the bourgeois character of the female thinker, warrior and superhero centuries after Radcliffe's day in the sun: writing about damsels, detectives and demon lovers (which we'll touch on here then explore in Volume Three when we examine TERFs and centrist media).

(exhibit 47a1: Detecting systemic trauma first requires something to detect and a detective to go about it, but historically involves various double standards and intersecting biases/privileges during liminal hauntologies [the sudden, seemingly magical and superstitious appearance of the Gothic castle]. Male detectives are renowned for their "superior" [sexist] intellect as a product of their male upbringing and socio-material advantages at being men, thus having access to better education. Female detectives from the Neo-Gothic period "won the lottery" of accidental birth, enjoying the [white, cis-het] role of princess trapped between their actual oppressors and those they fear as buried and scapegoated, but also conflated with: racial, queer and religious minorities. As things to continuously revive in the present, the rules of polite [meaning "heteronormative" enforcement] discourse would afford men certain advantages over women when exploring the perils of a Gothic castle, but both would be party to the larger scapegoating process: find the corrupt impostor and bury your gays to defend privatization.

For example, Ludovico from The Mysteries of Udolpho dispels the rumors of ghosts in the haunted room by staying in this supposedly "occupied" area with his sword. In the morning, he is gone. Ostensibly ghosts have spirited him away but in truth, pirates are to blame[!]. Yet, his dealings with them is cis-gendered, reflecting the dangers faced by men in such stories as commenting on the socio-material conditions of Radcliffe's time: Ludovico would more than likely not have to worry about being raped like Emily St. Aubert would [the Case of the Super Straight Pirates[7]]. Moreover, in defense of her own agency, Emily would have to rely on him and his sword to keep the rapacious, ostensibly heterosexual but also ambiguously gay pirates at bay [women not really being allowed to investigate their own trauma, but especially not allowed to do battle with it; re: that's what Amazons do]. But had she wielded the sword herself, she would have skewered her enemies with it, feminizing them like Dacre's Victoria, in 1806.)

(artist: Emma Layne)

That's the history of Radcliffe's refrain. Let's map its ongoing hauntological exploration of sex and danger (re: exposure of "virtue," left, as something to "armor" through swooning and amnesia—Radcliffe basically telling her audience to "think of the [white] women and children!"); i.e., as something to consider relative to the xenomorph throughout the remainder of the module (and not just this subchapter), on the edge of the civilized world.

In terms of sex demons and demon poetics at large, artistic playfulness is the "magic circle" (re: Zimmerman): of proletarian praxis in that it's "where the magic happens"; it occurs during liminal expressions of agency—i.e., in Gothic media, but also between reality and fiction through the subversion and transgression of various canonical rules and restrictions, during ludo-Gothic BDSM.

Keeping this in mind, let's look at some more historical "derelicts" of the demonic trifecta—damsels, detectives and sex demons as something traumatic to look on voyeuristically—in popular media at large, then bring this back around to Gothic expression as something to reinvent for our purposes.

We'll do so in an assigned order instead of a chronological one, looking at

- damsels as demonized, ostensibly disempowered chattel. We'll examine damsels in '80s porn with Nina Hartley and Victoria Paris (exhibit 47b).

- detectives seeking power and knowledge while fearing harmful torture. We'll examine different kinds of detectives, including Jennifer Lopez in Out of Sight (1998); i.e., as a militarized detective stemming from older, more passive and "chaste" forms that survive in the present; e.g., Velma Dinkley (exhibit 48a) as inspired by Radcliffe's classic formula, including nuns (exhibit 48b), but also more warlike detectives in different media types, such as Ellen Ripley (48c1) in cinema and Samus Aran (exhibit 40d1) in Metroidvania (whose respective, dangerous explorations of the Gothic castle present the closed space something to construct out of previously detected historical-material factors and warring xenophobic ideas: masculinity coming to rescue femininity, albeit grafted onto a female body that upholds the status quo and threatens to make her "rabid," thus needing to be put down faster than her male counterparts would; i.e., she becomes the thing she's told to kill).

- sex demons chattelized in semi-supernatural, semi-natural/animalistic forms that exist on the edge of the civilized world; i.e., animal demons from a wild, almost-primordial age. To that, we'll be looking repeatedly at the xenomorph—through Ridley Scott's reinvented, xenophilic forms of Gothic vision in the 1970s and 2010s (which we'll also expand on even more in the next chapter when we look at "lycanthropes," "furries" and other totem demons that continue to exist and mutate fabulously in the 21st century).

We'll also examine schools of thought that evolved out of an emerging Gothic discourse, which Scott would draw upon in his own work, but also many other artists before and after Alien. This includes Ann Radcliffe and Matthew Lewis investigating hidden, repressed aspects of their own society by using competing obvious narratives of demons, damsels and detectives inside their own derelict, ergodic stories of terror and horror media; i.e., a primarily white, middle-class corpus written by persons other than cis-het white men but now having expanded to other groups whose discourse wouldn't manifest until much later on, but arguably has connections to both author's vital "ancient" launchpads.

As we shall see, next, all of this came to a head with Alien, blending Radcliffean terror with Lewis-style horror to produce something altogether Numinous and splendid, thus wonderful at embodying the monstrous-feminine's various class/cultural tensions; i.e., the xenomorph is dualistic—was as much Radcliffe as Shelley, and working inside a shared aesthetic at cross purposes!

Footnotes

[1] Violence, for example, is Radcliffe's way of talking about sex through extensive innuendo; i.e., in the language of men, but from a woman's point of view seeing such things as "demonic. It's both not what she's talking about, and a paradoxical form of censorship that points to what she's getting at through associate violence (duels/demonic courtship). It's very virginal—like a comic book nerd who's either never had sex, or is camping the sex she has had to disassociate through demonic shows of force: "I'm not having sexual desires," Sampson might explain to Gregory (and by extension to us), in Romeo and Juliet (1597); "I'm cutting off the heads of the maids! Take in it what sense thou wilt!" (source). I genuinely can't tell with Radcliffe and that's the point; it gives her plausible deniability.

All the same, "demonic" clearly means the side of sexuality that women (for Radcliffe) can "only" experience through actual threat of rape. As such, Radcliffe's knife-dick demon BDSM features black penitents who demonstrably evoke courtly love as the "only way" a girl can experience passion outside legal marriage (which happens after the novel ends): on the receiving end of a lance, carried off on horseback or tied to a tree. Distress and ravishing of the damsel is classic courtship language, which Radcliffe translates to the summoning of demons through her stories to excite her and her readership: wish fulfillment per a Western, abject division with alienated, fetishized things that, per the ghost of the counterfeit, further the abjection process.

On one hand, it's code to dodge the censors; i.e., no different functionally than Mormon bubble porn or fruit emojis on social media exploited by the algorithm (as trans people are, for example). The more oppressive the system, the more restless and inventive the cryptonymy.

Radcliffe, for instance, unquestionably liked wilderness, castles, banditti and labyrinths (her search terms); these got her juices flowing. But they also contain/concern political attitudes (moral arguments), which said devices serve to camouflage in Radcliffe's work. As such, concealment and concern go hand-in-hand; i.e., all the actual heroes who appear good in Radcliffe's books despite their ferocity (or black outfit, below) are "white" and legitimized through revelation, and all the ones who are bad are delegitimated, Scooby-Doo-style when the mask is pulled off. So someone like Wesley in The Princess Bride, below, isn't really the Dread Pirate Roberts who ravishes women; he's the woman's dutiful servant saying "as you wish" while he gives her exactly what she wants through mutual consent!

Except, that's Rob Reiner adapting William Goldman's 1972 novel, which camped Radcliffe. By comparison, Emily St. Aubert in Udolpho gives all her inherited wealth to Valencourt, despite him not "rescuing" her until the very end of the book, and even then only appearing as an afterthought—penniless and dog-faced—because he gambled* all his money away and gave the rest to a man sharing his jail cell!

*Doing so in Paris, "a sinful city" according to Radcliffe (and an act, Sam Hirst once explained to me, that is synonymous with whoring around with women of "looser morals" than the heroine).

It sounds like a joke, except it's not; i.e., Udolpho isn't satire because Emily never shuts up about how she feels, and boy-oh-boy are her feelings not ambiguous! Yes, she's understandably pissed at first, but then not-so-understandably can't stay at her "widdle Vawencawt" because—golly gee whizz—he totally helped that one guy in a pinch while making himself destitute! In short, she (and by extension, Radcliffe) enables him and he (and by extension, Radcliffe) snow jobs Emily to basically vouch for codependency in her by feeding his addiction (because that's always healthy).

In turn, Valencourt is "heroic" not because he's actually strong or smart or even terribly good, but because Radcliffe assigns that position to him and makes Emily a bit dim to make for the storybook ending her middle-class readership thirsted for (saying as much about these bored housewives' actual marriages versus the ones they were clamoring for—a fact Jane Austen promptly and savagely parodied, in Northanger Abbey)! That's called "pandering" and Radcliffe was great at it.

Per Wolff, the Radcliffean Model is flush with the virgin/whore and hero/demon lover argument, but it's not ironic and—more to the point—conflates feminine desire with mutilative, unironic rape. Neo-conservative politics aside, the theatre's prescriptive nature is completely unhealthy. Through demon lovers and Black Veils, Radcliffe wanted all of these things in ways she could explain away and prescribe while upholding the status quo; through ludo-Gothic BDSM, we can ditch the dogma and keep the demons (and vaso vagal threats), camping her stories with passionate rape scenarios to lean into the most ironic, exquisite elements of "torture" she offered!

[2] Which I've written about in regards to; re: "Gothic Themes in Perfect Blue" and "Gothic themes in The Vanishing / Spoorloos" (2020). Jadis loved both those movies, for what it's worth.

[3] Said spaces classically written either anonymously by women—because women of the period weren't encouraged to write novels; i.e., as a respectable/profitable enterprise—or by sexist women adopting the pen names of men. "Ann Radcliffe" was already a penname (her real name was Ann Ward); by comparison, the Brontë sisters (not their brother, who didn't write much) used neutral-sounding pseudonyms under Queen Victoria's reign (Aton, Currer and Ellis Bell, the OG enbies), and Jane Austen (who died several years before Queen Victoria was born in 1819), used "by a lady" for Sense and Sensibility (1811), followed with "by the author of Sense and Sensibility" for her other novels.

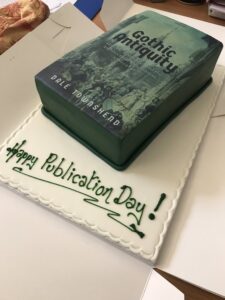

[4] One of my academic survivors for my master's (the one who said, "Nicholas, I'm happy to be your supervisor but just so you know, I've never played a computer game in my life!"). Dale's a nice enough bloke (as the Brits like to say), but also, I think he likes Radcliffe because he's a bit like her—not a Tory or anything like that, but a stay-at-home cat dad:

(artist: Dale Townshend and Dickens the cat)

On top of that, he also wrote a really cool book on Matthew Lewis, Matthew Lewis: The Gothic and Romantic Literary Culture (source tweet, DaleGothic96: May 14th, 2024), as well as Gothic Antiquity (source tweet, DaleGothic96: September 24th, 2019), which I've cited before in my own books (Dale's specially is Neo-Gothic architecture in fiction, which per my master's thesis, dovetails nicely with Metroidvania as ludo-Gothic):

(photographer: Dale Townshend)

and—while a bit of a ball-buster (the comments on my assignments were technically anonymous, but I could kind of tell it was him)—he also showed me kindness at school others sometimes didn't. He also wasn't weird about it when I came out, and used "Persephone" no problem at all. Thanks, Dale!

[5] Reminding me, once again, of Monty Python's Dennis Moore endlessly giving the poor starving country folk stolen lupins.

[6] "Oh, wow! A woman who can write. A female Shakespeare!" Puh-lease, Radcliffe doesn't have enough crossdressing or magic in her stories to be compared to Willie Shakes (now Lewis, on the other hand…)!

[7] Male queerness and queer theft of straight virtue being historically known to pirates through matelotage, a maritime practice between men that functioned like property ownership between male sailors not unlike a traditional, landbound wedding—a practice that Radcliffe wouldn't have been in the dark about; i.e., "any port in a storm."

***

Persephone van der Waard is the author of the multi-volume, non-profit book series, Sex Positivity—its art director, sole invigilator, illustrator and primary editor (the other co-writer/co-editor being Bay Ryan). Persephone has her independent PhD in Gothic poetics and ludo-Gothic BDSM (focusing on partially on Metroidvania), and is a MtF trans woman, anti-fascist, atheist/Satanist, poly/pan kinkster, erotic artist/pornographer and anarcho-Communist with two partners. Including multiple playmates/friends and collaborators, Persephone and her many muses work/play together on Sex Positivity and on her artwork at large as a sex-positive force. That being said, she still occasionally writes reviews, Gothic analyses, and interviews for fun on her old blog (and makes YouTube videos talking about politics). To learn more about Persephone's academic/activist work and larger portfolio, go to her About the Author page. To purchase illustrated or written material from Persephone (thus support the work she does), please refer to her commissions page for more information. Any money Persephone earns through commissions goes towards helping sex workers through the Sex Positivity project; i.e., by paying costs and funding shoots, therefore raising awareness. Likewise, Persephone accepts donations for the project, which you can send directly to her PayPal, Ko-Fi, Patreon or CashApp. Every bit helps!

Comments

Post a Comment