Let Us Pray (2014) by Brian O’Malley is a cross-cut narrative, largely accreting from its Final Girl protagonist. She’s tough, but inexperienced; wears a tank top and sports a perpetual, brunette ponytail. As a movie gimmick, this character archetype hasn’t changed much since Ellen Ripley and Laurie Strode helped make it famous, in the late 1970s. Still, it’s been indiscriminately trotted out, over the years, by self-aware outings like Wes Craven’s

Scream (1996). Others were less transparent when utilizing it—even if remaining somewhat tongue-in-cheek, amid the solemn act.

Let Us Prey is one of those.

To be frank, it doesn’t jump the rails; it adheres to a formula, executing it straightforwardly as it focuses on the gory mess (the star of the show apart from Cunningham). The movie doesn’t deign to concern itself with parody or pastiche, instead treating the act of shooting blood and goo as an art, in and of itself—an art form perfected by the likes of Stuart Gordon in his early days, hashing out messy Lovecraft adaptations like Re-Animator (1985) and From Beyond (1986) with the help of Jeffery Combs; or James Cameron, treating Aliens (1986) as his primary showcase in the gore department, which in, hideous monstrosities are reliably displayed with great care, including the alien queen’s egg sac—brought to life with cheap-but-inventive props: garbage bags first filled, and then coated, with maple syrup.

In the case of

Let Us Prey the more narratively-inclined viewer might turn their nose up at such visual dross.

However, a diehard gore-hound like me found little to complain out,

given how few horror movies nowadays actually bother getting this

concept down. Believe it or not, there’s a trick to shooting gore—a presentation, much like a dish served to a customer at a restaurant. Alas, as an art form, it’s never been one to get much respect outside of smaller horror circles.

No, to win awards, you have to dress violence up. It has to be

about something. Very often this is done in historical dramas. Think

Glory (1989),

Braveheart (1995), or

Saving Private Ryan (1998). Great care goes into their collective, violent spectacles. The havoc within is regarded as purposeful precisely because it drives the narrative. As such, the splatter in

Braveheart exudes substance purely by virtue of its protagonist, William Wallace, being an oppressed Scot who beheads English generals for “freedom.” Similar value is unfairly ignored in things that really splatter—against walls, or peoples’ faces. Drama snobs (or gangster aficionados) would declare that splatterhouse lacks imagination, while, at the same time, insisting their own violent-driven genres somehow transcend violence for violence’s sake. They think their entertainment abjures or eschews a ghastly approach for something more sublime or dignified.

Personally I think this distinction is rubbish.

The Godfather (1972) or

Goodfellas (1990) are fine movies, but they’re still obsessed with violence, and rely on it to attract an audience; the chief difference lies only in how it’s viewed. Yet, for fans of those movies, violence without narrative structure amounts to little more than a geek show.

I disagree, here, as well. Gore is only a geek show if it’s truly disgusting. On the other hand, gore as art is different because its aim isn’t simply to shock. For example, a bespectacled soldier in

Tropic Thunder (2014) is “gutted” for the camera. The bayonet retracts and he, forlorn, reaches into his stomach, pulling out handfuls of spaghetti. The effect is not entirely sterile, but it is also addressed by director Ben Stiller as not being intentionally disgusting in the same sense as George Romero’s disemboweling scene, in

Dawn of the Dead (1978). Here, gore is neither a geek show, nor solemnly wedded to narrative, but a parody of something older. It’s a spoof, meant to poke fun. The same cannot be said for the infamous “horse head” scene, in Coppola's

Godfather. It’s dead-serious affair, one that revels in the slaughter (and, to boot, uses a real head, not a prop).

There’s no harm in this (the head was from an already-dead horse); violence and gore are always a means to an end. At the same time, frowning on the treatment of these variables as an end, unto themselves—this comes off as a tad contrived, to me. No, a reverential approach isn’t somehow “lesser” or “minor.” It just is what it is.

Thus, there is a fourth taxon to which Let Us Prey belongs: celebration. To this, it behaves like a deliberate, careful study of gore and splatter. There really isn’t much else going on, to be honest. As said, the heroine is a straight-laced, no-nonsense brunette who does her job. She’s the rookie cop, the same sort on display in Anthony DiBlasi’s Last Shift (2014). Such movies often have a siege element. So do these two. Think John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) or Steven Kostanski’s The Void (2016). Usually this operation involves a police station that is in some way or another being decommissioned, or repurposed; or is built on top of something older or dead. It’s the Law versus ghosts, ghouls, Terminators or Great Old Ones.

Let Us Prey puts a different spin on this scenario: the station is populated by cops and cellmates who are equally tarnished; it’s essentially a madhouse run by the mad. Of course, this isn’t obvious at first. The buddy-cop duo are breaking protocol by having sex in their cruiser whilst on patrol. Regardless, this doesn’t automatically make them murders... right? Little time is wasted establishing pretense, here, however. Instead, everyone is morally-dubious from the get-go. The surprise, if there’s any to be had, comes from just how far-gone they really are. It’s not so much a twist, either—not when Liam Cunningham shows up to play Santa: he knows who’s been naughty or nice. It’s not long before we do, too.

I

suppose his job is somewhat simpler than usual given that no one in the

movie is what I’d call “nice.” Just about everyone (except for the

heroine) starts off slightly bad, only to morally implode as full-blown

deviants, come the movie’s abrupt, violent, and vague conclusion. The

key figure amid the deplorable frenzy is also the movie’s only

recognizable face: Liam Cunningham. Horror films generally cast

no-names, to begin with, relying on single veterans to carry the banner.

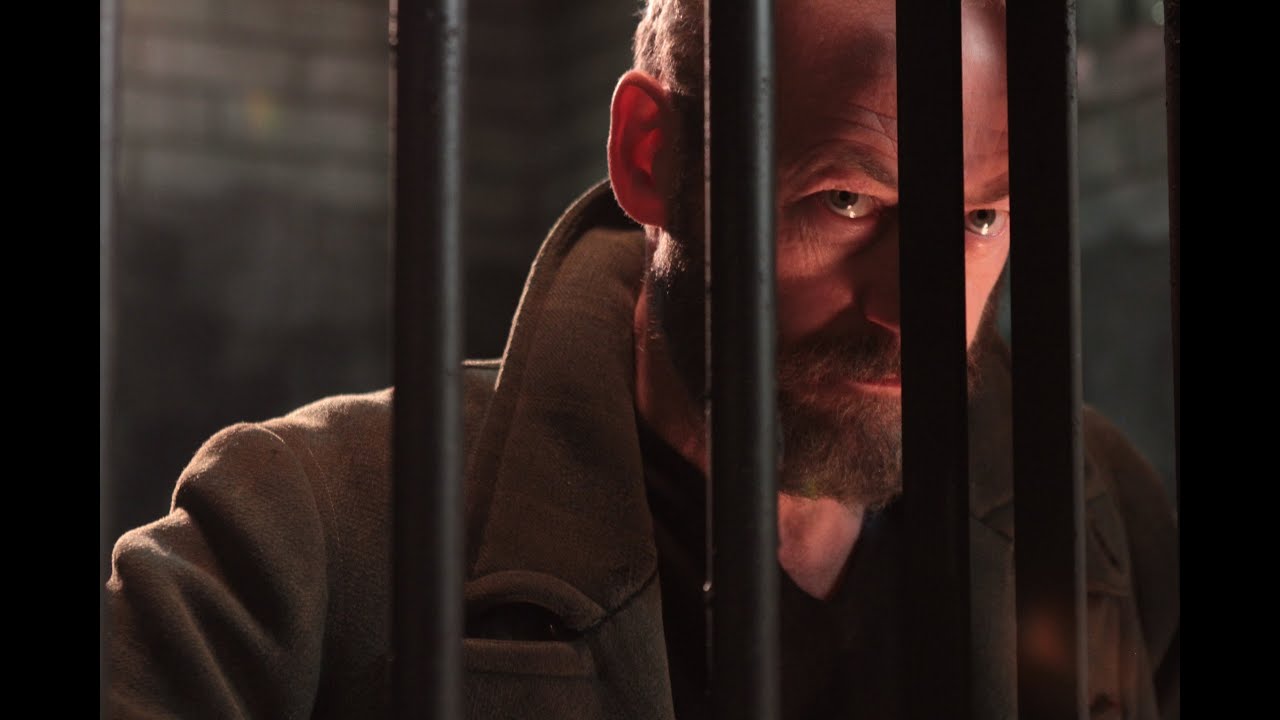

Cunningham is up to the task, reliable-as-usual as a nameless, severe

man presaged by a murder of crows. He disappears and reappears on a

whim, simultaneously carrying a book, on the pages of which a great

number of names are ominously scrawled.

What’s

the book for? Why is he there? Alas, his dialogue is curt and

enigmatic; it would hint, rather than explain. All the same, Cunningham

isn’t a blank slate. In fact, for a man whose facial expression never

seems to change throughout the movie (or ever), he manages to

communicate a great deal. His eyes bore into those around him; those

persons squirm. Likewise, his posture, stance and voice ferry energy and

knowledge into what could have been a perfunctory exercise: simply

standing still and looking gruff. One must inject gravitas into what is

effectively very little.

To this, Cunningham excels. Think Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name… except if that person were Satan. Eastwood’s Blondie from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) stands around and waits, chewing the scenery of a jail cell until it catches fire or explodes. That’s basically what happens here: a bunch of crooked cops are turned inside-out, and the one person who isn’t a murderer or rapist swears allegiance to an individual who likes to “do things the old-fashioned way.” They seal their pact with a kiss, as the cesspit behind them burns to the ground. Roll credits.

Again, there’s little in the way of plot, here. There’s no twist. The Man comes around, and the sinners meet their end. It’s a little like playing Clue in that you expect someone from the group of equally-suspect individuals to be culpable and eventually found out—except all parties, here, are equally deranged. In fact, the wife-beater is just the start, ensconced like the wooden core of a Russian doll as each person surviving him eclipses his crimes with their own (the worst of them being perpetrated by the “good Christian” man who runs the station). As each is revealed, the violence mirrors the crime exposed, culminating in face-removal via a floor-mounted shoe-polisher.

And let that be a lesson, folks: always assume that any object in a horror movie can serve as the proverbial Chekhov’s gun. In Phillip Noyce’s Dead Calm (1989) it was a shotgun; in Gerard Johnstone’s Housebound (2014), a cheese grater; in Mike Flanagan’s Hush (2016), both a high-pitched house alarm and wine corkscrew. Anything can be weaponized. The shotgun wielded by Prey’s chief villain felt a little pedestrian, but the shoe-polisher showed some inventive flair. As an example of splatterhouse, I felt the movie positively excelled as an example of gore “for gore’s sake” done right.

Watching it, I was reminded of Cigarette Burns (2005), the eighth episode of the short-lived miniseries on Showtime, directed by Mick Garris: Masters of Horror (2005-7). In it, Norman Reedus (of Walking Dead [2010] fame) sits in a projectionist’s basement, the two of them discussing “cigarette burns” (a tell-tale analogue cue for when a new reel is spliced in). During their chat, the topic of “lesser genres” inevitably comes up: fantasy, science fiction, and horror. What the episode explores, I think, is that each of those has its own sub-genres that are frowned upon, even harder. I think Let Us Prey is a good example of what would generally be listed as an already “lesser” genre’s “weaker” half. I also think it’s done right, with just enough artistic flourish and expert straight-face (from Cunningham) to make it memorable.

***

Persephone van der Waard is the author of the multi-volume, non-profit book series, Sex Positivity—its art director, sole invigilator, illustrator and primary editor (the other co-writer/co-editor being Bay Ryan). She has her independent PhD in Gothic poetics and ludo-Gothic BDSM (focusing on partially on Metroidvania), and is a MtF trans woman, anti-fascist, atheist/Satanist, poly/pan kinkster, erotic artist/pornographer and anarcho-Communist with two partners. Including her multiple playmates/friends and collaborators, Persephone and her eighteen muses work/play together on Sex Positivity and on her artwork at large as a sex-positive force. She sometimes writes reviews, Gothic analyses, and interviews for fun on her old blog; or does continual independent research on Metroidvania and speedrunning. If you're interested in her academic/activist work and larger portfolio, go to her About the Author page to learn more; if you're curious about illustrated or written commissions, please refer to her commissions page for more information.

Comments

Post a Comment